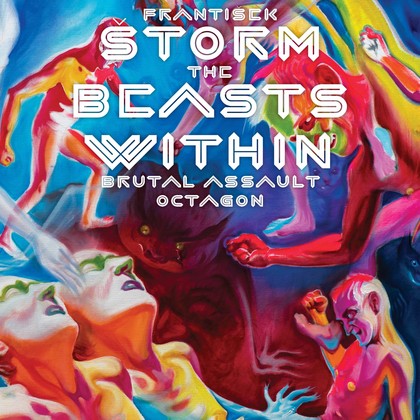

The Beasts Within / Brutal Assault 2025Exhibitions

The inner beast, clad in vibrant colors and electronic beats, swells, smolders, and erupts on stage. The relentless sense of madness in today’s world compels me to reflect—as a defense mechanism—through creation. Life, death, and resurrection as a psychedelic comic strip. A consciousness shifted by art feels more real than this building: the Prussian troops heading south simply bypassed the Josefov Fortress; today we generate energy here from extreme music and extreme art that connects people from all over the world. The strategic importance of this place has never been greater than it is now.

Painting and music share only one thing: I never studied them. But what binds music and visual art is design, which I did study—and it quietly informs my approach to themes: illustration, metaphor, play with symbols, words, sound, color, and movement. Many of my animated phenakistoscopic drawings were created as designs for songs—some even before the melodies existed for the lyrics. I designed my own guitar and crafted original fonts for all our album covers: Gesamtkunstwerk is the diagnosis.

Themes in my work come and go with whatever idea, brush, guitar, or synth I manage to keep hold of. Maldorör Disco, a band born as a one-off karaoke act for exhibition openings, unexpectedly morphed into a new Master’s Hammer record, which we are releasing this year. Angel of Slime is the name of another cycle: Pectinatella—a jellyfish-like creature—is the ideal object of decadent worship: so hideous it becomes beautiful, a vessel into which one can project both celestial horror and the bliss of warm jelly. The third and latest body of work is a developing Stations of the Cross, a real commission for an actual church. I approached Christ’s final journey as a deeply personal story—what may look like a selfie is in fact an attempt at self-reflection.