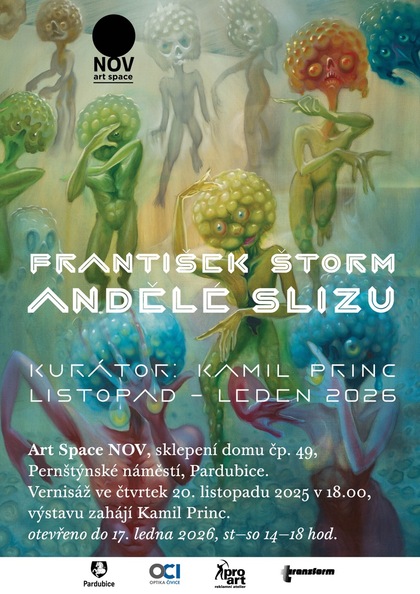

Angels of SlimeExhibitions

Pardubice, October 2025, photo: Štěpán Bartoš.

The word “angel” comes from the Greek expression “ἄγγελος”, meaning “messenger” between man and God. But what form does God have? According to Plato’s dialogue Timaeus, the most perfect geometric body is an oval sphere. Everywhere in the universe we can find spherical objects – stars, planets, moons, black holes… And also slippery, slimy and vehemently drooling organisms occupying murky stagnant waters buried under a sickly veil of fog from poisonous fumes. Yes, we mean the slimy loaves (Pectinatella magnifica) annexing the ponds in Štorm’s place of residence, which have become the artist’s gooey muses and swollen guides to Dante’s Virgil’s Inferno. The similarity to the whispering green fairies that appear after the unbridled consumption of absinthe is also not purely coincidental. The Bochnatky, as an inexhaustible source of Štorm's inspiration, truly seem to come from noumenal spheres and transcendental planes to bring us a new gospel of the true nature of things "an sich", where beauty means something other than what is expected and usual. "Abomination is not an obstacle, but a goal," as the exhibiting artist declared.

The atmosphere of corrosive sulfuric hazes is also evident, for example, in the painting Island in the Mist, where the author draws on Böcklin's Island of the Dead. Here he mixes gloomy aesthetics with the artistic tendencies of Theodor Kittelsen, who adores anemic transience and distortion of contours, captured in the hlaváček-like, tender scenery of this melancholic canvas: “In the autumn gloom, soaked in fog, / the moon shines gold in the cloudy glass, / and in the dim light of the lamp pulled down / all its contours are so faintly blurred.” (b. Impromptu). The water surface forms a metaphor for human consciousness, where the sky represents the superego and the world of ideal forms, while the lower part forms a rippled image full of slimy loaves as the low instinctual sphere of the subconscious, where repressed traumas and impulsive id hold the reins.

References to Baudelaire's "artificial paradises" of hallucinatory drug states can be found in the painting The Old Tribe (Psilocybe arcanum), where the author depicted himself as a corpse rotting in the landscape as an homage to Rimbaud's poem The Sleeper in the Hollow. From his decaying body, psychoactive lycopods sprout, bringing the coveted laudanum as a medicine against the saddening mundanity of life. The never-ending cycle of death and rebirth continues, however, and the human deceased becomes an abundant source of nutrients for many plants and necrophagous animals. As was the case in Erben's ballad Záhoř's Bed, death can also be a cleansing of sins and a new beginning in a different form, because all living things are only modes of one all-pervading divine essence of Spinoza's "Deus sive natura".

Kamil Princ, October 2025